Provoking radical

fidelity

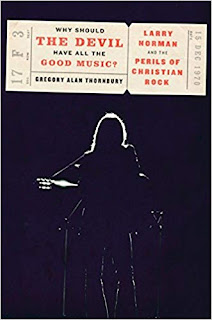

Why Should the Devil

have all the Good Music?

Larry Norman and the

Perils of Christian Rock

Author: Gregory Alan

Thornbury

Publisher:

Convergent Books

Pages: 292

Imagine being given

unlimited access to the papers and archives of an artist that you

have listened to for many years. One of the fascinations of Why

should the Devil Have All the Good Music? is what Gregory Alan

Thornbury chooses to include. So much could be said! Then there is

the challenge of what to make of it. The peaks! The valleys!

After watching the

documentary Fallen Angel: The Outlaw Larry Norman, where

Norman gets “shot down,” I was crestfallen. Even here, the

reminders of indiscretions resurrected those dark feelings that like

ghosts haunt me once again. Nevertheless, I am thankful to get an

alternative view to Norman’s life,

one that feels more balanced.

If that is not

reason enough to read this, the writing is superb; the thought

incisive. The Norman estate made the right choice in opening the

vault to this author. So much of the history of Jesus Music is here,

which makes this essential reading for any interested in the

intersection of faith and rock. It’s utterly fascinating.

Even though some of

Norman’s dreams and visions were never fully realized, it’s a

pleasure to behold his more noble ambitions. If as some say, God

gives credit for right aspirations, Norman must have gained

commendation. Despite the ways that he fell short, as we all do, his

goals pointed him toward praiseworthy ends. It’s something that I

needed to see in light of Fallen Angel.

In Another Land

was my introduction to Norman’s recordings. By the time that I

made my way to So Long Ago the Garden, I was still new to the

Christian faith, having more zeal than knowledge. After the

straightforwardness of Another Land, I was perplexed by

Garden. Why so few overt

Christian references? Reading about the background and aftermath of

this release enables me to see that Norman was badly misunderstood

and judged. It make me think of the quotation on the back of the dust

jacket, “I was both happy and unhappy to have Larry Norman’s

earthly arc fully explained. How the hell did he survive all that?”

(Black Francis, songwriter and lead singer of Pixies). I am grateful

for the explanations, but sorry that I was among those who questioned

Norman’s judgment on this controversial release.

An

insight from Norman

sheds light on what is

a long time coming among Christians:

Music is a powerful language, but

most Christian music is not art. . . . It never relies on—in

fact it seems to be ignorant of—allegory,

symbolism, metaphor, inner-rhyme, play-on-word, surrealism, and many

of the other poetry born elements of music that have made it the

highly celebrated art form it has become (98-99).

As

a new Christian, uneducated about the world of art, I had no concept

of the elements described by Norman. Fortunately, over the years

there has been more instruction on theology and the arts. Otherwise,

like the proclamation of the gospel, how can we know unless someone

tells us?

This

book does not try to reconcile the contradictions—something

only God can do. It’s aim, like Norman’s ministry, is to provoke

an encounter leading to radical obedience. Curiosity, superficial

engagement and maintaining the status quo are insufficient. Norman

was aiming at an authentic following of Jesus.

Perhaps

Norman’s life is a reminder that we dare not miss this pursuit.

What

we get right or wrong is of little consequence in

comparison.

The

world needs to see more

of Jesus

in the life of his followers.

I

think Norman will be pleased if the totality of his life inspires

toward this end. So if you read this book and/or listen to Norman’s

recordings, think about what it means for

Jesus to be the way, the truth and the life.